Inflation's Branding Issue

Inflation is the destruction of a currency. The rise in price level is a side effect.

Inflation has a branding problem. The word 'inflation' makes it sound like something, whatever it is, is getting bigger. The things that get bigger during inflation are prices or more generally the price level of everything in the economy. This is the wrong focus. The focus ought to be on the money which is disintegrating. Inflation is the destruction of the value of money and a decrease in inflation is just a reduction in the speed of that destruction. In other words, even though inflation is down from 9%+ to 5%, the money is still disintegrating in your pocket while you walk around.

Money is a unit of measure and as such, some of its value derives from its consistency over time. At its heart, money is a measure of human time-value. Does your time-value change drastically from day to day or week to week? Does it naturally go down over time or up? Imagine baking a cake every month but the definition of a cup of flour changed with each attempt. Regardless of what we call inflation in the future, it should be regarded as currency phenomenon and not a price phenomenon.

Reverse treadmill

Maybe a good way to think about what inflation does to our efforts is to imagine a moving walkway at a big airport. Normally we get on those in the direction they are running in order to get to our gate more quickly. Sometimes they are stopped and are exactly equivalent to the floor next to them. Now imagine that you got on one going opposite its direction of travel. Aside from thoroughly annoying your fellow travelers as you slalom past, you would make slower progress to your gate. If it is going slower than you can walk, you'll still get there but with more effort. If you aren’t keeping up with its speed, you end up where you started and never get to your gate. This is what it should feel like to us to operate in a world with a positive inflation rate. Prices are constantly rising because the value represented by a unit of money is constantly falling. Deflation is exactly the opposite. Deflation is getting on the moving sidewalk going your way. Prices drop, so all things equal, you can afford more with your savings. You get to your gate with less effort. That doesn't sound like such a bad thing to me but perhaps we could start with trying to target zero inflation, ie. "price stability" like it says in the Fed's congressional mandate.

This begs the question, why do we have an inflation target? Why do folks at the Fed try to target low, persistent inflation, currently 2%? In other words, why do they think it's good for the American people to be on a treadmill which is slowly pushing them backward? This story is fun so let's get into it.

Inflation targeting is born

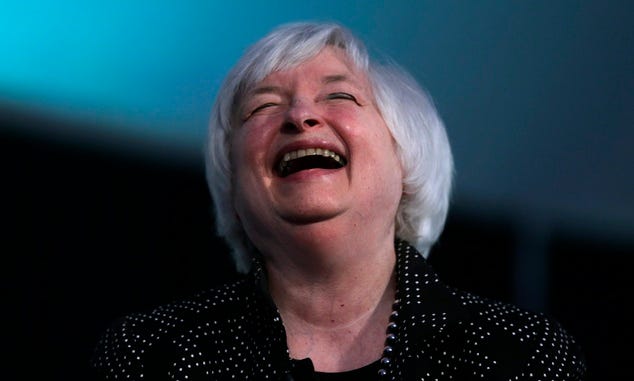

In 1996, then Fed Governor and voting member of the FOMC, Janet Yellen made what she called the "greasing the wheel's argument" at the July FOMC meeting with Alan Greenspan presiding (p. 43-46). In this argument, she claims that:

...a little inflation lowers unemployment by facilitating adjustments in relative pay in a world where individuals deeply dislike nominal pay cuts. With some permanent aversion to nominal pay cuts, the output and unemployment costs of lowering inflation that we ordinarily think of as transitory simply never disappear...

Supporting this argument, Yellen cites a Brookings paper by Akerlof, Perry, and Dickens where they put forth the claim that, "An aversion on the part of firms to impose these desired nominal wage cuts results in higher permanent rates of unemployment." The paper argues against the notion that "some politicians and economists want the Fed to go further and to pursue zero inflation as its primary goal" because "zero inflation would be a permanent reduction in gross domestic product of 1 to 3 percent and a permanent drop in employment by the same amount."

This paper was a response to a proposal in the Senate to simplify the mandate of the Federal Reserve from its existing mandate of “promoting effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates” to a single mandate: “promote price stability.” Ie. just focus on the price level / currency and nothing else.

The researchers came to their conclusions by simulating an economy with thousands of firms and modeling what would happen in their simulation if the firms couldn't cut wages under various inflation regimes. Their model produced a correlation between low inflation and high unemployment. This is consistent with the, then in vogue but now discredited, Phillips Curve which predicts that low inflation will drive up wages and lead to high unemployment. They backtested their model on historical data to determine its predictive power and it seemed to correlate both with postwar and Great Depression era outcomes.

One need look no further back in time than the past decade and a half since the Great Financial Crisis and the loose monetary policy since to see that persistently low inflation did not correlate with high unemployment but with historically low and declining unemployment. It wasn’t until the pandemic shock that we got an appreciable move in either metric.

If actual experience disagrees with the principle upon which a policy is based, shouldn't that policy be revisted and possibly changed? Shouldn't we trust observation of reality over a toy model of the economy developed in the 90s?

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that the future Nobel Laureate, George Akerlof who lead this research is and was at the time, Janet Yellen’s husband. Is it a conflict of interest to promote the work of your husband in a policy setting meeting without disclosing the relationship for the record?

A joke at our (literal) expense

I'll leave you with sense of Yellen's great sense of humor. She got a good laugh recorded into the minutes of that 1996 meeting (emphasis added):

Very recently, Bob Schiller of Yale posed the following question to a random sample of Americans. He asked, "Do you agree with the following statement: I think that if my pay went up, I would feel more satisfaction in my job, more sense of fulfillment, even if prices went up just as much." Of his respondents, 28 percent agreed fully and another 21 percent partially agreed. Only 27 percent completely disagreed, although I think it will comfort you to learn that in a special subsample of economists, not one single economist Schiller polled fully agreed and 78 percent completely disagreed. [Laughter]

It's hard not to read this as an rather cruel indictment of the ignorance of us noneconomists and a simultaneous admission that economists recognize as obvious that an increase in a wage that matches an increase in the price level is the same as getting nothing at all.

We are all walking against the treadmill while those in charge of the economy are laughing at us.

There are countless ways to try to twist reality to argue inflation is bad.

Inflation, for the right reasons, is good.

Stagnant, unfair, and failing economies have low inflation.

The reality is that great, dynamic, and fair economies have some inflation.

When the US entered WWII, and transformed their economy, massively increasing GDP and eliminating the malaise of the depression, inflation resulted.

Saying inflation is the erosion of savings is equivalent to saying that inflation is the forgiveness of debt.

In an over leveraged world, we need more inflation.

In a world where we need to transform the economy to reduce our environmental impact we need more inflation.

Disintegration. I think that's how we need to talk about it!